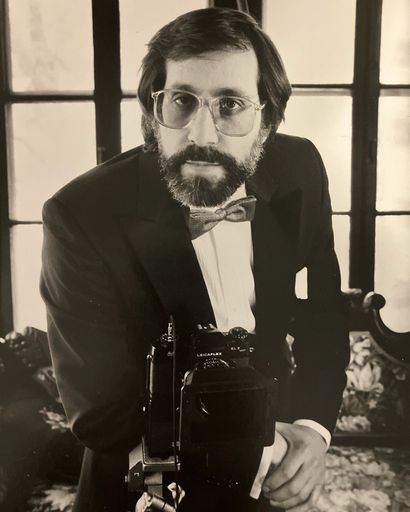

Harvey D. Edwards

December 24, 1947 — October 22, 2024

Berwyn

Harvey D. Edwards

The celebrated artist Harvey Edwards, creator of the iconic image Leg Warmers, died peacefully, surrounded by family on October 22, 2024.

His life was devoted entirely to the artistic pursuit. He created photographs, paintings, and sculptures (and even wrote the occasional poem) uninterrupted from the time he shot his first roll of film at age twelve until several months before he passed at the age of seventy-six. The closest he came to holding what might be seen as a traditional job was taking a part-time position as a forensic police photographer for two years in a small Long Island town. His need for stability was always exceeded by his artistic curiosity and desire to engage with the world on his own idiosyncratic terms.

Harvey was born in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Pearl (née Tropper) and Leonard Edwards, a mechanic who would later move the family to Massapequa to own and operate a garage. At eighteen, he joined the Air Force to become an aerial photographer but was discharged weeks before deploying, after his father’s sudden death. Moving back to Massapequa he began working as a photographer’s assistant to Eric Pollitzer, spending much of his time traveling between artist studios in Manhattan, documenting their work for galleries and museums. He began working as an assistant for one of those artists not long after, mixing paint on weekends for the painter Roy Lichtenstein.

Traveling between professional working artist studios, Harvey saw firsthand how life could be built around a creative practice, and soon he began to experiment with the materials at hand, dropping paint from the garage roof onto appropriated storm windows from his childhood home. He had his first solo show at Les Fleurs Gallery which eventually led to investors willing to take a chance on his distinctive vision. In a surprisingly short time, he opened his gallery at 222 E 58th Street in Manhattan. It was at his opening here, in the new space, that he met his future wife, collaborator, and muse of fifty-one years, Eleanor, a fashion designer. They married three months later.

Soon after, they moved to Los Angeles where Harvey began exploring and photographing the Fairfax community; a small neighborhood in West Hollywood comprised of displaced and dispossessed holocaust survivors. He spent over two years capturing not just faces but objects, gestures, and fragments of routines — evidence of lives being lived in the aftermath of unimaginable loss. The final collection of photographs was edited into the seminal photo book “Fairfax.”

During a show at Limited Edition Gallery, Harvey‘s poster advertising the show had sold out and he quickly discovered a new, important medium for his work. He started printing his photographs mainly as posters, elevating the poster from being a means to promote works of art to be the work of art itself. A random encounter with a dancer on the street in Los Angeles inspired Harvey to start photographing ballet, a chance event that would culminate in the creation of the now-renowned images Leg Warmers, Hands, and Slippers. The next year, in 1979, Harvey was interviewed for the first time by the Los Angeles Herald; a symbolic recognition that he had arrived. From his start documenting the work of other artists in New York, he would now be chronicled himself.

Seven years after moving to Los Angeles, they moved back to New York where Harvey continued to lead a growing interest in posters, touring nationally and exhibiting extensively. He has since sold over a million copies of Leg Warmers.

Taking advantage of the access granted by his cousin, the American Ballet Theater dancer Bruce Marks, Harvey put his photographic skills in service of laying bare the unrelenting work and determination required to become a professional dancer. Shooting for several years at The Joffrey Ballet, New York City Ballet, American Ballet Theater, Boston Ballet, and the Dance Theater of Harlem, the photographs that followed captured the brutal work of dancers, before the make-up and behind the perfected performances. The images he produced were not the glossed, public-facing veneers meant to hide the labor of practice; they revealed the beauty of practice alone. The collection of photographs from this period would form his next book, “The Art of Dance,” published by Little Brown. These images have become a staple of our visual grammar regarding dance and the unseen, often unacknowledged, determination required to pursue a meaningful craft. At this time, and in the years that followed, he created a number of images that came to define his career as a photographer and, unknowingly, changed the trajectory of the art poster market itself.

He often said, “Without art, what is life.” This was an internal truth that oriented his life with a consuming sense of immediacy. As much as a person can be defined by a single facet of their life, in the multitudes a person may contain, he was an artist before anything else. For Harvey, art was less a career than a condition—an innate, inescapable response to being alive.

This devotion was also, in its way, a form of generosity: if he had even the slightest resource — time, space, energy—he gave it freely to those he loved. He was politically active and created many photographs visualizing his opinions and connecting as an ally. Most importantly, Harvey didn’t just give what he had; he gave who he was — wild and alive — without hesitation and often without a filter. Always the life of the party, he entertained everyone with his big, boisterous personality. His uninhibited expression was a kind of offering in and of itself, giving permission to those around him to be their authentic, unedited, selves. He loved to surprise unsuspecting guests who came into his house with one of his many mannequins, and once drove the whole family two hours away to a L.L. Bean at 3 a.m. simply because it was open 24 hours a day.

In death, Harvey is survived by his three children, Brooke, Lauren, and Garet; his wife Eleanor; two sons-in-law and a daughter-in-law, Todd, Eric, and Lauren; a sister, Marilyn and a brother-in-law, Paul; three grandchildren, Alyssa, Taylor, and Lee, all of whom affectionately called him “Gampy;” seven beloved nieces and nephews; as well as a brother-in-law, Eric, and sister-in-law, Dorothy.

He left us a world more full of art than before, and the art of living a life without compromise.

Guestbook

Visits: 195

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors